One of my all-time favourite books is I Know You Got Soul by Jeremy Clarkson. I have been quite verbal in my admiration of Clarkson, both online and in real life; seeing him on television as a little boy ended up inspiring a lot of my writing style, so my choice shouldn’t be much of a surprise. In this book, Clarkson discusses various machines that he believes have soul, something I’m sure us watch fans can relate to. I mean, we feel something deeper for these machines that extends beyond simple appreciation for mechanics.

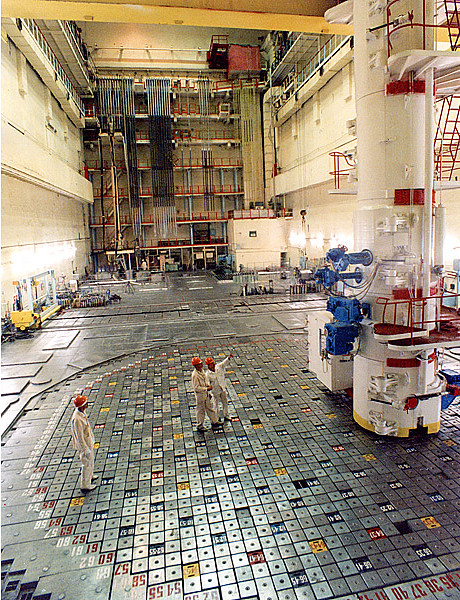

Anyone can appreciate a machine. Machines serve us, so why wouldn’t we appreciate them? A waffle iron is a relatively simple machine designed with one express purpose in mond: to make delicious waffles Gérald-Genta-style dials. A nuclear reactor is a rather complex machine designed with one express purpose in mind: to provide clean energy without making everyone bleed from their eyes and grow an extra leg. Can a waffle iron have soul? Maybe. I think it differs from person to person. Some people may feel an attachment to old, reliable waffle irons that fed nations without faltering. I know that the waffle iron in the kitchen cabinet is worth more to me than the sum of its parts; it has memories attached to it.

So does this all stem from memories then? No. One can’t have memories for things that one hasn’t experienced. I don’t have memories of the Battle of Hastings, because I wasn’t there. One can have nostalgia for things not directly experienced. This is called anemoia. That’s the reason that I imagine myself so vividly in a long, beige, American-made personal luxury car smoking a cigarette after doing some less than legal things. I have never smoked. I have never spent any amount of time in a long and beige American-made personal luxury car. Despite this, if I got knocked out in a gnarly bar fight and lost some of my memories and a doctor asked me if I was driving a Buick Gran Sport on the evening of June 5th, 1969, I would likely answer with a yes.

Does that mean I like watches because they are simply tools that aid in my fantasy of living in the past? Maybe. As much as I would love to feel what a brand new watch was like in the 60s, I understand that life is generally better today. The world is more free and more people have access to clean water and proper food than before. I would still like a Buick Gran Sport though.

Here’s where sciolism comes in. If you are a theist, you probably believe that humankind was created by some higher being. If we build watches, don’t we sort of become the higher being? If we can have a soul by virtue of our creation, is it totally out of the question to assume that watches have souls? It is, because I don’t believe that watches are sentient nor worship us. I hate to burst some bubbles here, but there is probably no watch afterlife either.

I have a point though, don’t I? Could our love for watches be the same as the love between a creator and the created? I believe that our attachment is for that reason; we recognise watches and timekeeping to be an achievement of our species and take pride in it. This idea has some holes in it, because I don’t see too many light bulb enthusiasts out there.

In an effort to explain our love for watches, I have simply proved the point that myself and just about every other enthusiast has made: our love for watches is, for the most part, inexplicable. We’re humans and we like shiny things. Some like watches more for telling the time, others aesthetics, others flexing. At the end of the day, we see them as more than the sum of their parts, whether that’s due to anemoia, repressed fantasies or just plain enthusiasm.