I recently purchased two lighters from an auction platform I’m quite active on. They’re old Colibri things, one is a Colibri Jetric that looks quite stylish; I don’t care for the other one as unfortunately it does not work. I think it’s a faulty piezo. Anyway, you’re here for watches, so I’ll add that with these lighters I received a Swatch chronograph. I didn’t pay for it, instead, the owner of the business was really quite thankful for my support, so threw in a watch that he had laying around. As something of a watch salesman guy myself, I understand, respect and admire acts like this, as customer satisfaction is the core of a small business.

I never mentioned that I was a watch repairman/watchmaker, so I considered this to be a lucky stroke or the stars aligning. The seller told me that it was broken, but, ever the optimist, I was hoping a simple battery replacement would get it going.

I wouldn’t be writing this if all it took was popping in a size 399 cell, because that’s hardly watch repair. Sure, you feel like Breguet himself when you get it right on your first try, but as soon as you do anything more, you’re a fish out of water. Swatch makes battery changes really easy, I’ll give them that. Well, easy if your local currency fits the coin slot. No current South African coin fits the slot. The 20c is close to thick enough with curvature that’s not too bad, but it’s too small to get a grip on. The new R5 is too thick. The old R5 has the right curve, but is too thin. What was the most readily available coin that works for me? A 1952 2 1/2 shilling that the watchmaker gifted me. A flathead screwdriver scars the cover and I don’t see Swatches often enough to justify buying one of the special tools to open them, so my shilling will have to do.

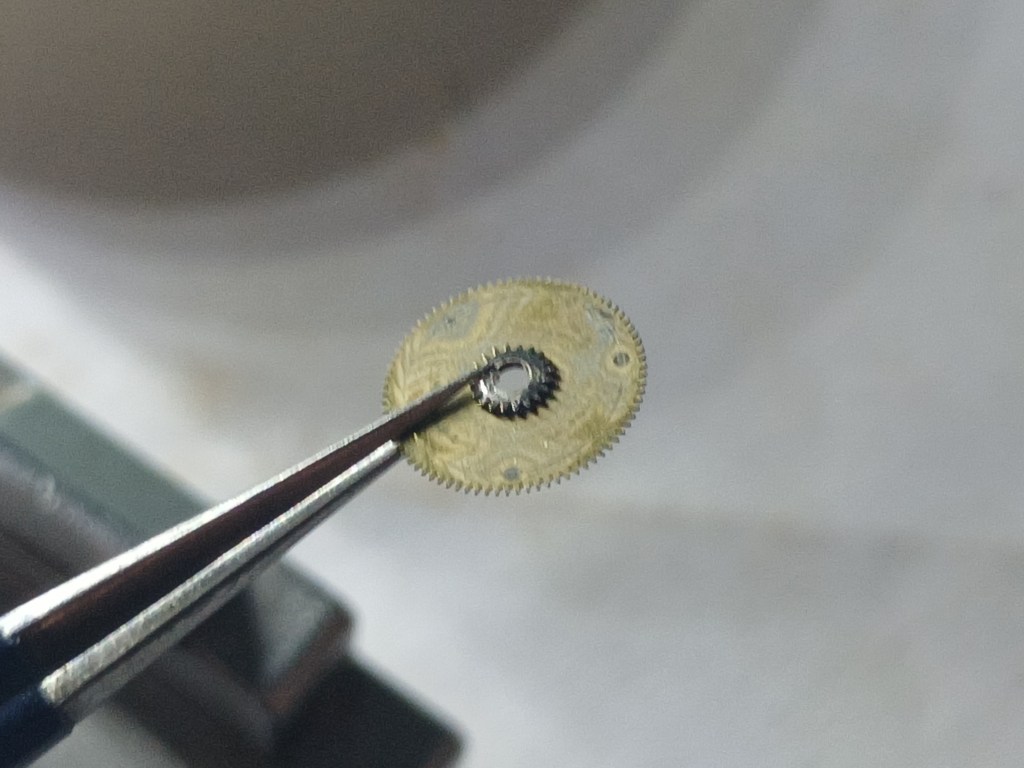

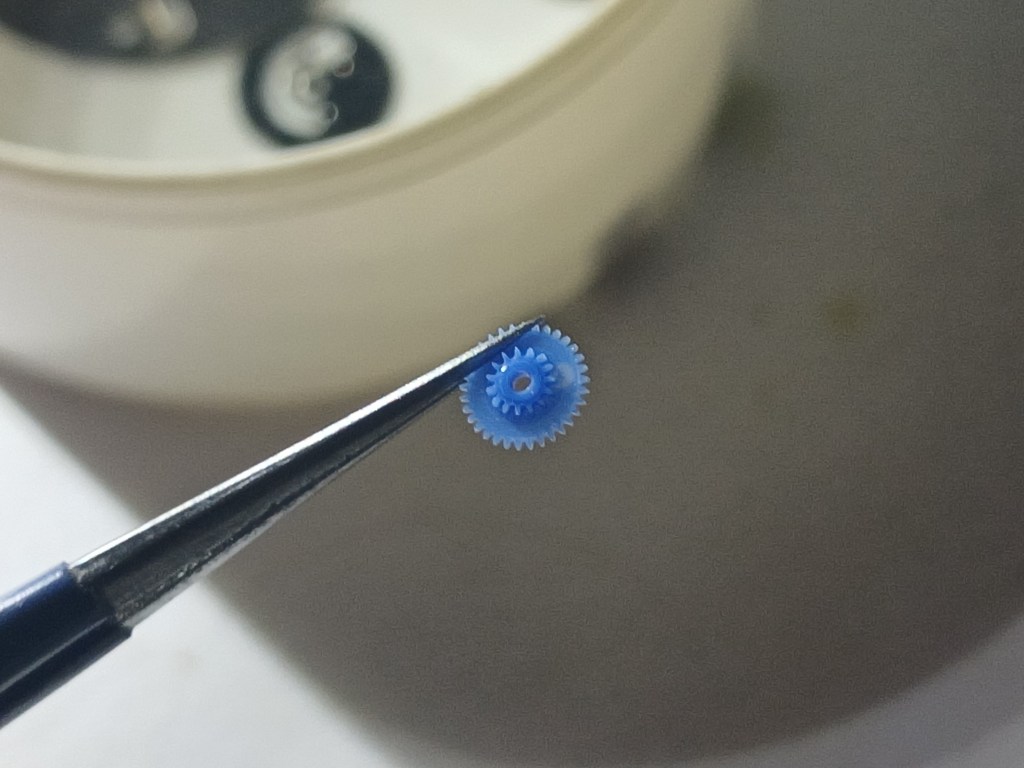

If a new battery didn’t work, it had to be something in the movement. How does one open a Swatch? Well, it’s complicated. The bezel pops off with a caseback knife. I don’t have a very thin caseback knife and if you don’t either, you are virtually guaranteed to scar the case. That can be fixed; no skin off of my nose. The crystal is a monster. A crystal lift claw tool thingy won’t pull it off. Believe me, I tried with everything I had. You have to use your caseback knife to pry it off. The dial? Glued on. That’s not too uncommon, but one of my watchmaking pet peeves. Then the s*** really starts to hit the fan. The date disc retainer plate is not screwed on, but effectively riveted on with melted plastic. You have no other choice but to break this seal to remove all of the dial side components.

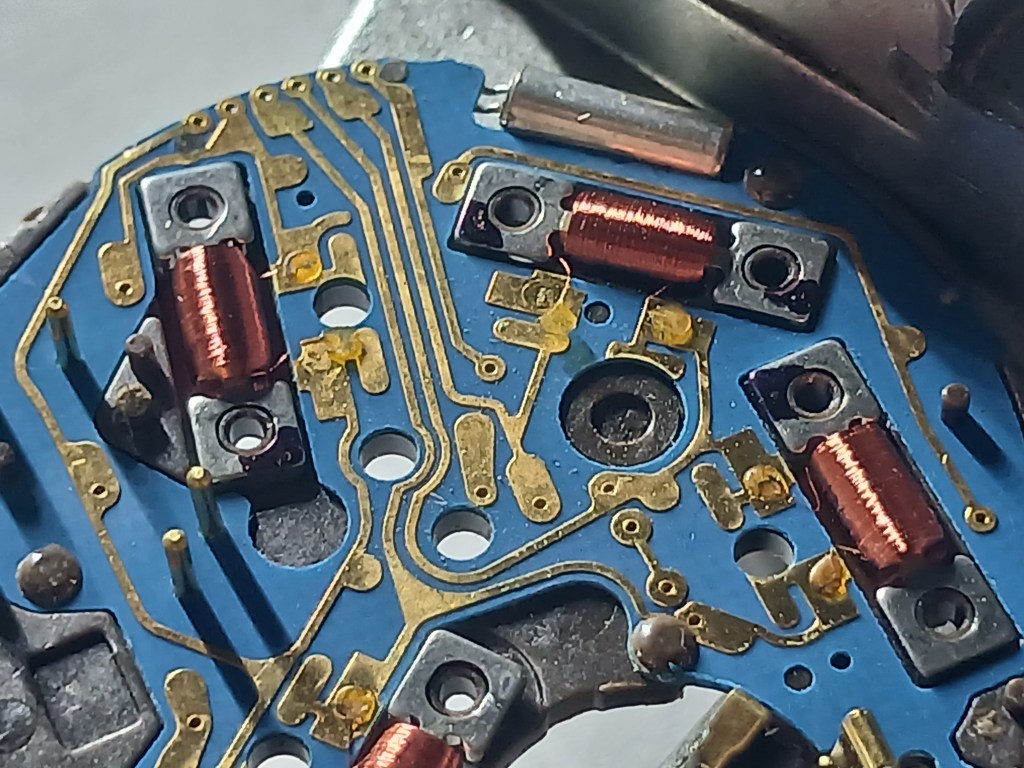

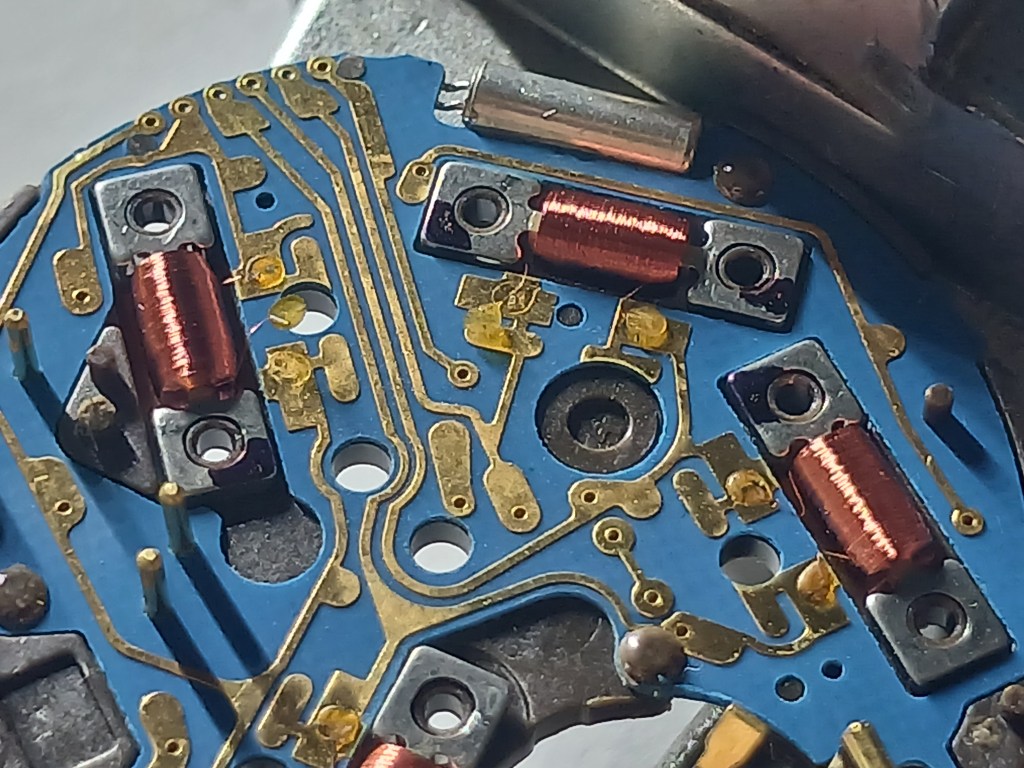

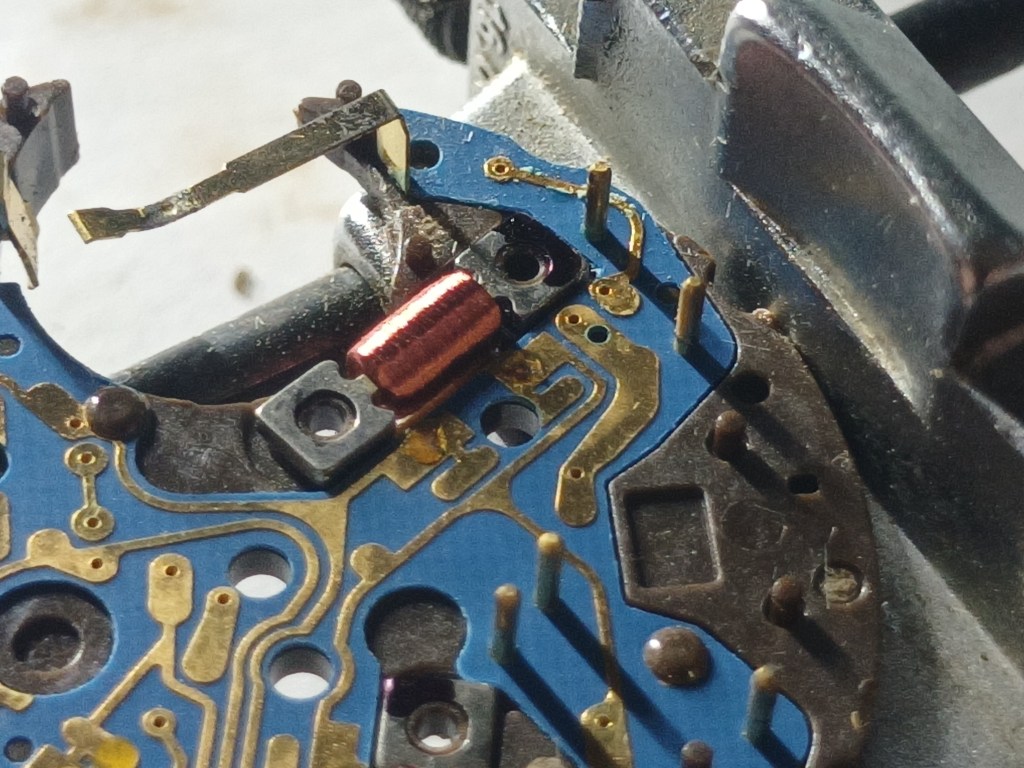

What’s more is that the same is true for the entire movement. No screws, just plastic rivets. You have to painstakingly scratch all of them off and pry the plastic movement plates apart to access the circuit board and connections. A lot of these rivets are right by the coils, which puts excrement in the pants of most watchmakers, as coils will break if struck witch a screwdriver or tweezer with enough force. They are extremely sensitive and are too much effort to repair.

That’s another thing, effort. Where does one draw the line between disposable and salvageable? Personally, I believe that nothing is ever disposable. Old Timex movements can still be repaired, it’s just a little trickier than a quality watch movement. The same is true for BFG pin-pallets. I have two 866s on my desk running very well as I write. I consider myself lucky. As horrible as they can be, they can still be disassembled and reassembled, although I prefer “servicing” them without taking them apart at all. Every watchmaker has a limit to the amount of effort that they are willing to put in. Let’s call this the Effort Coefficient™. My Effort Coefficient™ is quite high, because I don’t value my time as much as a professional watchmaker does. Whether this Swatch gets fixed tomorrow or in thirty years’ time is no bother to me, but for a watchmaker who has a few watches on his workbench that all need attention, this is important. Being able to service and troubleshoot a watch in two weeks time means that he gets paid. Most of my jobs are essentially volunteer work or hobbyist tinkering, so putting food on the table isn’t my primary concern. This is why many watchmakers these days refuse to work on pin-pallets— it’s just too much effort.

I cannot charge a customer 100 USD to fix a 125 USD watch. Sometimes I have to, but, being a hobbyist, I try to keep my prices as low as possible because the joy of tinkering and the joy of knowing that another little machine will bring someone else happiness is the real payment. Most people aren’t prepared to pay real watchmaker rates where I live. If I had a shop to run and saw a pin-pallet come in, I would understand why watchmakers refuse to work on them. They experience greater wear, which means one might have to put the screwdrivers down and source parts. All of this requires a lot of chatting with the customer about money, which is my least favourite part of the job. Then there’s the construction. Most pin-pallets aren’t designed to be easily serviced, so it’s reasonable to think that one may make more mistakes whilst working on them. This usually means more spare parts will be needed, which will have to come out of one’s own pocket. Then there’s reliability. Three months guarantee was the gold standard fifty years ago. Sometimes one has to ask oneself if a freshly serviced pin-pallet can even survive that long. They can, but if they don’t, it’s another expense.

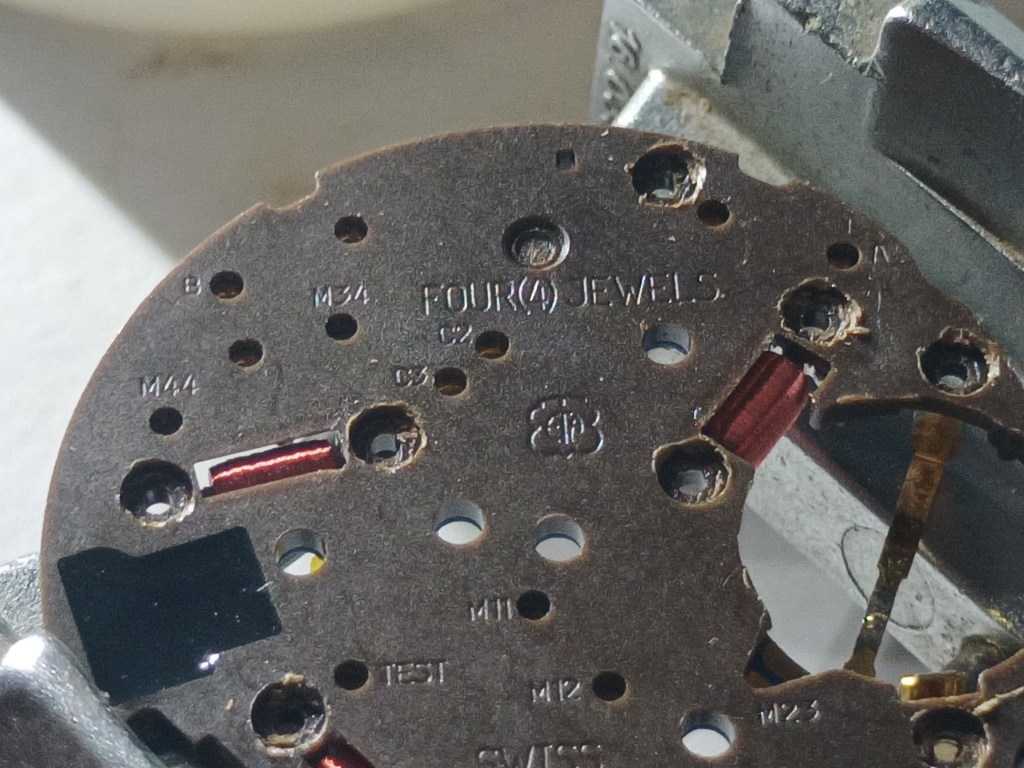

Back to the Swatch. The watch appeared to be water damaged judging by the film on some of the dial side wheels. The dial is strangely unscathed. Water means corrosion on the circuit board. When the green stuff is cleared off, the watch usually comes back to life. This one had deeper problems. The connections from the coils to the board were mostly severed. These appear to be soldered on, which is another very time consuming thing to fix, seeing as I don’t have any low-temperature solder and also have never really soldered before. The copper wire connections are also scarily thin, so much so that cleaning with my soft brush would break them.

Below the circuit board is the mechanical bit of the movement. Finishing is spartan to say the least.

This watch definitely went swimming. I’m sure many of the problems could have been mitigated by not letting it sit for so long. Oh well, it’s not like they would have repaired it thirty years ago…