From remarks given on the occasion of the 90th Anniversary of the Housing Authority of Charleston:

Nostalgia is an odd phenomenon. We now see it as a wistful feeling for times past, perhaps better or simpler times. That was not how it was originally intended. The term was coined in the 17th Century to describe debilitating homesickness among Swiss mercenaries. So, I would caution against nostalgia for the deep past as we celebrate the Charleston Housing Authority’s 90th Birthday.

The 1930’s began inauspiciously. Businesses and banks failed. Men, mostly men, lost jobs. Many fortunes were lost, but at the bottom rung of the economic ladder conditions were much worse. A group of eight women sought to expose the worst slums in Charleston. Places where the conditions had horrific health outcomes, overrun with vermin.

In 1932, with one in four wage earners out of work, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt gave a speech at Oglethorpe University in Atlanta to lay out the economic plans for his new administration. In that speech, the President correctly noted that the economy of the future would be driven by the consumer, not the producer, and importantly, he called for “bold, persistent experimentation” to address the countries ills. Substandard housing was just one of those ills. Fully 48% of households had no indoor plumbing.

In early 1934 the General Assembly allowed municipalities to create Housing Authorities and later that year the City Council of Charleston authorized the creation of the Housing Authority of Charleston. That was formalized in May of 1935, and that is why we are here today. In that year the newly formed Public Works Administration chose Charleston as one of its first projects and Meeting Street Manor, just a short distance from here, was built. In 1937 Robert Mills Manor was constructed and after destruction caused by tornadoes, Gadsden Green followed in 1938. These projects constituted “bold, persistent experimentation” for the 1930’s.

But experimentation did not end there. In the coming decades, the CHA would expand its footprint and incorporate different models of public housing. The CHA would expand outside of the peninsula and bring its mission of safe, comfortable and affordable housing to communities far from the city center. The CHA was an early adopter of scattered site housing that helped knit neighborhoods together despite differences in earning capacity. Along the way, in the 90 years of its existence, a happy and perhaps unintended consequence of CHA’s efforts, true communities were born. Certainly, better than those squalid slums that they replaced.

(The point of modern public housing is not to look like public housing.)

Over the past several decades the size of the CHA has remained relatively consistent, with slightly more than 100 employees. In the 90 years of its existence the CHA has only had six Executive Directors, a number that indicates persistence and stability. It is the quality of these public servants from the Executive Director through all facets of the CHA that makes the CHA work for the people of the City of Charleston as it has for these many years.

I will end with a prediction and a quick anecdote. In ten years’ time, at the celebration of the CHA’s 100th Anniversary, we will have lived through the most transformative period in its history, including the decade of its founding. Plans have long been in the works. Projects have begun or are about to begin, that are going to change the perception of affordable housing in Charleston forever. Long-held opinions about CHA are going to shattered. I hope that I will be invited to say “I told you so” to those assembled.

At our most recent meeting, a resident rose to speak at the time in the meeting devoted to citizen participation. This is not meant as a “give and take” or “question and answer” period. A resident will usually point out a potential problem and the administration is there to hear it and address it as needed. This particular resident was worried about potential changes and renovations in CHA properties. He prefaced his remarks by saying that the 18 years that he had spent in Robert Mills Manor were the happiest of his life and that he had a safe and well-maintained unit, and when he opened his front door, he was surrounded by physical beauty. I could only answer him by saying that as good as it was, through the efforts of the people who work for the CHA, it was about to be even better. Thank you.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Of course, I took the folded speech out of my pocket, made a big display of placing it on the lectern, and never looked at it again. I just improvised and took most of those points out of order. I told some jokes for levity’s sake. I was supposed to close the ceremony, but the Executive Director made us switch positions, so I led off.

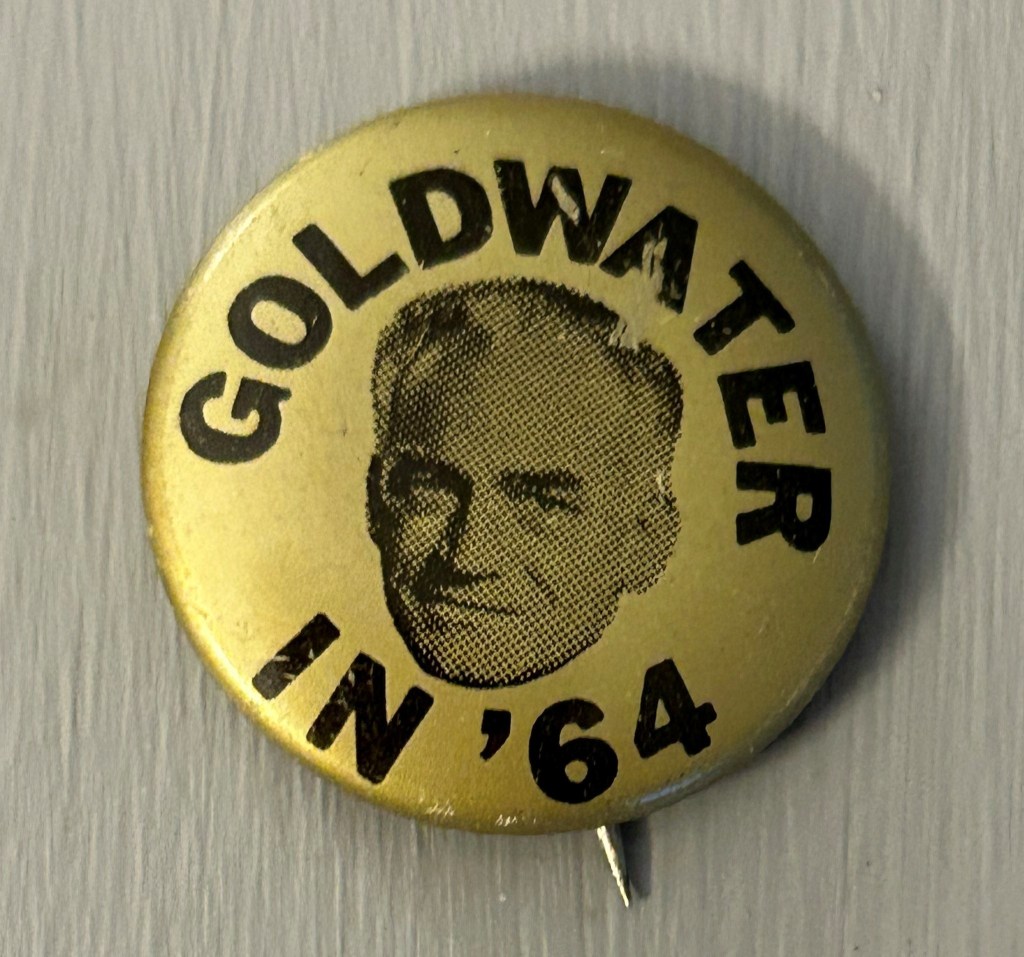

(From my father’s small collection of non-New Deal, non-Great Society ephemera. Again, not fans of FDR.)

So that is another thing that I care about. Housing policy, that is. I have since I was a teen. I grew up in a family of FDR haters, and I here I am taking a central speech of his to prop up my own anodyne points. I am a strong free marketer, a small “L” libertarian with no particular party affiliation, a cultural contrarian, and a Bill of Rights absolutist (just try to quarter soldiers in my home, no way) with an unhealthy appreciation of quasi-socialist New Deal policies. I go out of my way to visit Works Progress Administration and Civilian Conservation Corps buildings and artwork.

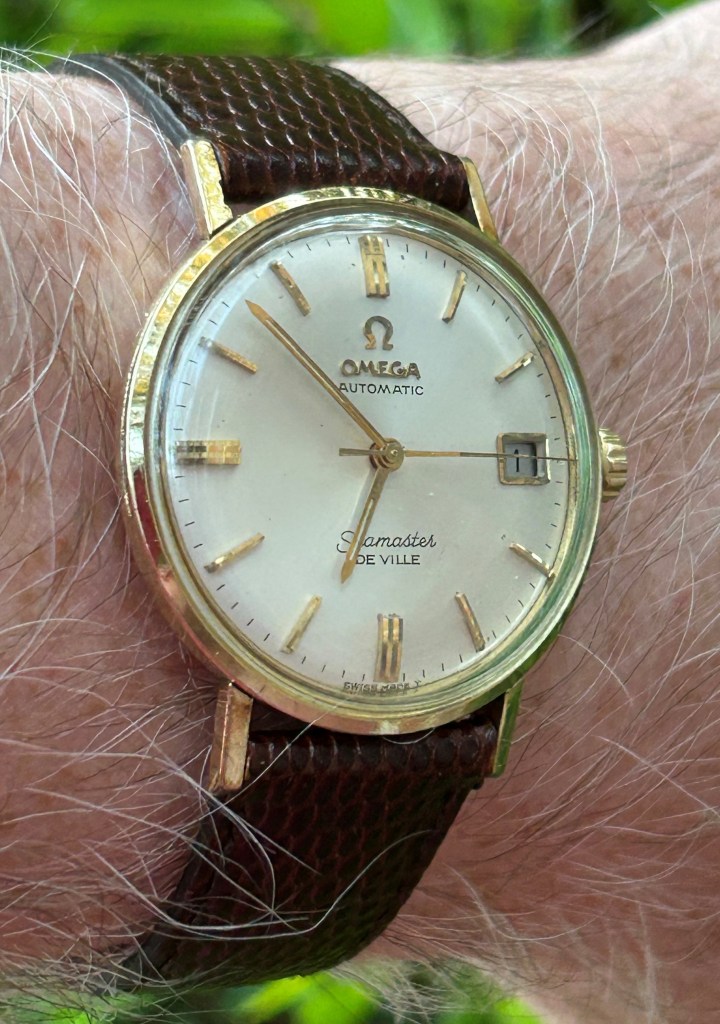

When I speak, and it matters, I wear my grandfather’s old Omega Seamaster DeVille. I have worn it through many trials. When it failed a few years ago during a big out of town murder trial, I drove back to pick up another gold watch. It was my everyday watch for a decade. Today I would probably reconsider that decision and leave it on its pillow most days. I put a lot of unnecessary miles on it. Having one indispensable watch is what we sentimentalists do.

(I recommend this for a non-hagiographic treatment of the era.)