This is perhaps one of the restorations I am most proud of. All it took me was a day to get it from a watch even the seller said was in “bad shape” to a beautiful and rare watch with a special connection to my hometown.

Now, how did I get this watch? After I wrote an exam on Tuesday, I had to get a new passport. The whole family went to the nearest Home Affairs office that wasn’t laden with lethargy, phlegm and the skeletons of those still in line. On the way there, we passed a place called Cowboy Town. Cowboy Town is basically a few old buildings dressed up to look like they’re from an Old Western film. It’s a great place to stop for a beer and a pie. They also have a used car and caravan lot. What interested me was a Facebook Marketplace listing that had been up for aeons for an Ernest Borel Chamber of Mines watch.

One the way back home, we stopped there and I walked into the shop. I asked the kind shop assistant lady for the watch and she took it out for me. Something else also caught my eye while doing a light bit of browsing: a Revue pocket watch. Revue made good watches back in its heyday. My pocket watch predates its golden era of the 1960s, but is still very solid. I won’t go into too much detail here, as it will take me about a hundred thousand years to get it going; I’ll post about it when I do. I need a balance staff and a screw. The screw will have to be remanufactured and the balance staff will need to be fitted by someone with more finesse than a ham-fisted toothless South African oaf. Honestly, I don’t know if Revue still exist today (I think they’ve rebranded as Revue Thommen) and I’m willing to bet they they’re a shell of their former selves owned by some faraway company. I don’t really care about modern Revue, but I’m willing to change that if someone can show me that they make anything worthy of interest.

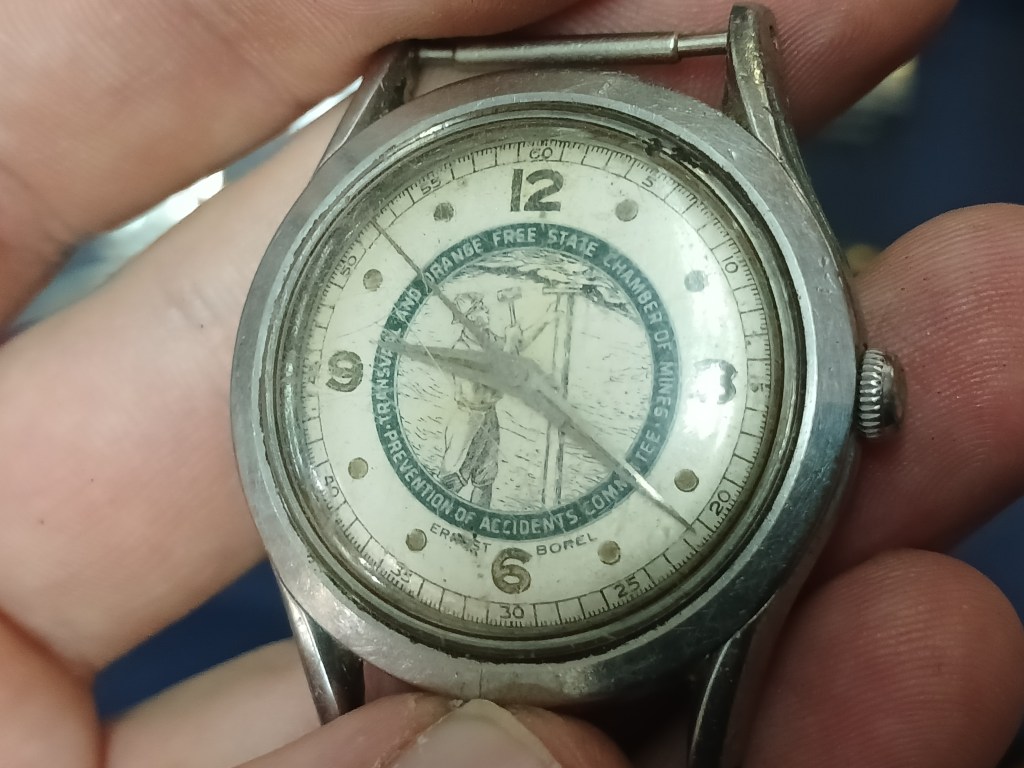

Back to the Ernest Borel. To put it simply, South African mines, which employed literally every living thing in my town (my whole province, actually) had safety competitions each year. Through this safety training, my paternal grandfather performed CPR on his family dog after an accident. I believe that there was even mouth-to-mouth if I recall correctly. The winner of these safety competitions would be given a watch. These were always stainless steel Ernest Borel automatic watches. Quite the gift, I imagine. The dial was a custom affair, with a man hammering a chock or block of something between a beam and the top of the shaft. Around this image would be some text. There is some variation, but the gist is the same. Some dials have the province listed (I have only encountered dials with “Transvaal and Orange Free-State” printed, which were the most mining-centric provinces) while others do not. Dials were printed either in Afrikaans or in English. My dial is printed in Afrikaans and doesn’t have the province listed. The text was, “Chamber of Mines of South Africa Prevention of Accidents Committee” or “Kamer van Mynwese van Suid-Afrika Kommitee vir die Voorkoming van Ongelukke” in Afrikaans.

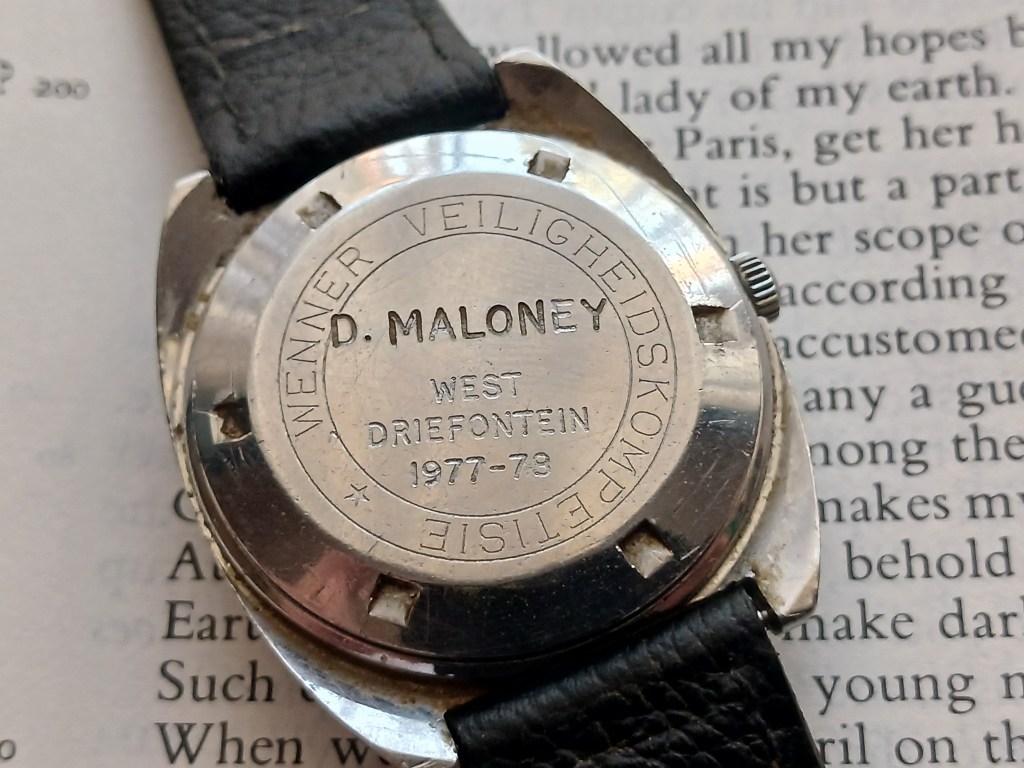

The caseback was engraved “Winner Safety Competition” or “Wenner Veiligheidskompetisie” with the name of the winner, the date, and the mine name engraved in the centre. My watch was won by D. Maloney in 1977 – 78 at West Driefontein, which is/was (f*** knows if they’re still going) a mine close to where I live. Politics have seen the names and borders changed so many times I may as well live on Mars. What province am I in? Depends on whether the person you ask lives in the present, the 1990s, or the 1960s.

There were two “generations” of these watches from what I can tell. Earlier models were fitted with Felsa automatics, while later models packed ETAs. These watches are fairly scarce. They come up for sale once in a blue moon and there are quite a few of them, but a not-at-all-insignificant number of them have been lost to time. It’s kind of a running gag/cruel joke between my watchmaker and I that miners almost never took good care of their watches. When a miner’s watch graces the workbench, it’s likely not going to be a cakewalk. If a miner owned it, it’s likely to come in with any of the following: destroyed hairspring, melted glass, rusted-out movement, destroyed dial or in a state of such dirtiness that you may gag when working on it. As we know, stereotypes aren’t always true and many miners did take good care of their watches, especially the solid gold Omegas, Zeniths and other brands that were issued to them for long service. Many also took those gold watches underground. I believe that old dress watches are very capable, but cyanide water and rock falls are a little too much for them.

I had never held a Chamber of Mines Ernest Borel before I bought mine. I did handle a dial before, but that was it. I have been looking for one for a while now, at least a year. I passed up a good one which wasn’t engraved at the beginning of the year as I just wasn’t sure if the platform it was being sold on was secure enough. I missed out on another one that went on auction just a few months ago. The price was too high for the condition it was in. This one was as close to perfect as could be; in other words, it was just barely good enough.

First impressions were bad, which was good. I wanted the watch to be s***. I wanted it to be in as bad a state as possible, but still redeemable, in order to get a good price on it. It needed the force of ten elephants to hand wind. The hands were misaligned. The crystal was broken. The rotor banged against the caseback harder than… I don’t think this metaphor needs completion.

Once I did rent ten elephants and wound the watch, it sprung to life. This was good, as I then knew that it was at least complete. I am a hopeless addict to haggling, so I made sure to get a tiny bit off the price, just for a kick. I haggled the price down by approximately 4 USD, which means I effectively got the busted-up Revue pocket watch for free. Watch Math™.

I spent the car ride home holding my vomit in looking at the wrist gunk and playing with the crown. It needed a service, big-time. Would you hazard a guess as to what the movement looked like when I got the caseback off? Spotless; pristine. Another interesting fact made itself known to me upon reading the inside of the caseback, where the spec-sheet was engraved. “Super Water Resistant Tested 600 Feet.” I saw “feet” and immediately began pleasuring myself. Once I had the workbench cleaned up, I got the bright idea to actually test this watch for water resistance. I didn’t have a waterproof testing machine thingy, but I would make a plan.

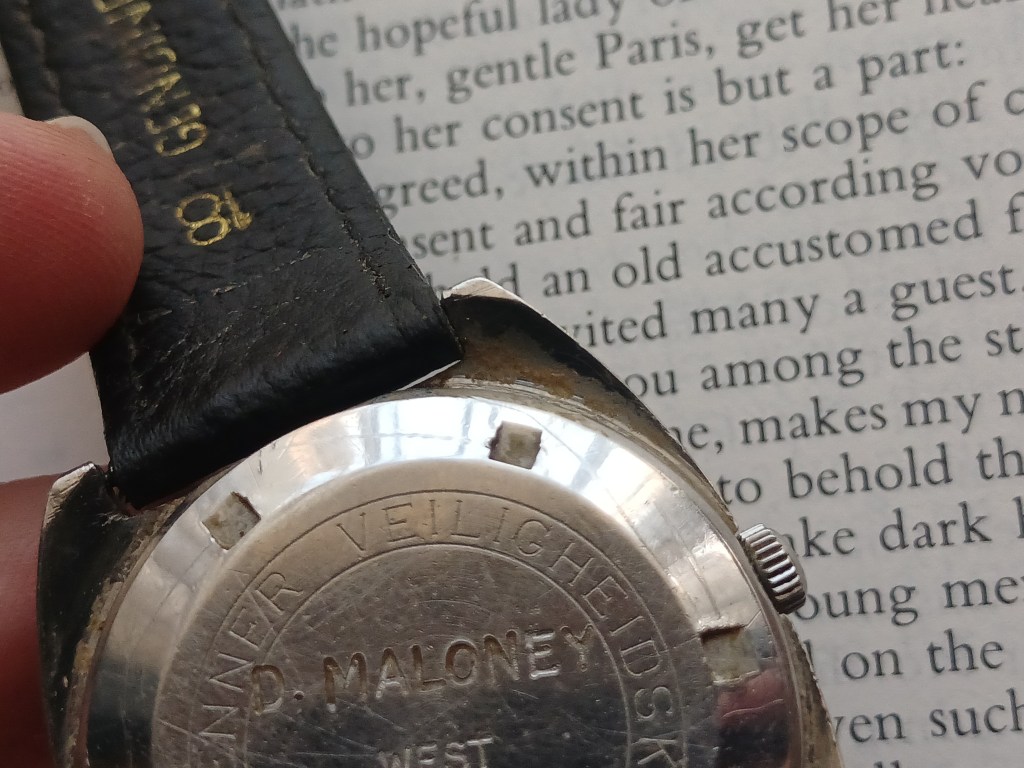

The first step of the restoration was removing the blobs of metal on the case. Mr Maloney was definitely welding with this watch on. They came off quite easily and I sanded the whole case with some 1200 and 2000 grit sandpaper. It only really made a difference on the front face, but I’ll take it; it’s better than nothing. I’ll get a buffing wheel and some proper compound eventually. The next step was sorting the movement out. It ran surprisingly well given the condition the rest of the watch was in, but it needed a service nonetheless as the date wasn’t changing over. Once the movement was serviced and the broken date jumper wheel or whatever it’s called was replaced, another issue presented itself: a loud clicking when winding the watch. It was random, so it wasn’t the teeth on the winding pinion. It wasn’t the reversing wheels, as it would make the sound even if the automatic works wasn’t fitted. It wasn’t the mainspring slipping either. How did I resolve this? I didn’t. If you hand wind it enough it still makes the sound. I’ve read that this series of movements had a method of releasing excess torque, so I think it’s that system in action. If the movement disintegrates soon, then I’ll know that I was wrong and that there really was an issue.

The automatic winding works was a pain too. Donald de Carle blessed us with the fourteen commandments for watchmakers in his famous book Practical Watch Repairing. Commandment number fourteen reads as follows:

Finally, do not run down another horologist’s work, even if it leaves something to be desired. If the condition of a movement is in question, treat the matter diplomatically; describe what you can do to improve it, do not give an opinion that somebody else has done a poor job. Be prepared to stand by your own results; that is your reward.

I am sorry, Mr de Carle, but you will have to allow me to break this commandment for a moment.

The guy who fixed this watch up did something. I don’t know what his plan was, but I hope he achieved his goal. The wrong screw was screwed in to hold the rotor down, likely contributing to the massive amount of play and also destroying the threads entirely. The wrong screws were used as case screws, likely damaging those threads too. The watch doesn’t even need case screws. I have made right everything wrong, which included fitting an entirely new (well, used,) automatic works that had no play in the rotor at all.

Once the movement was working, I decided to put it on the timegrapher. Those who know me know that I don’t actually own a timegrapher, so I used the app on my phone. Without me even regulating it it ran extremely well, easily within five or six seconds a day. Amplitude is very high. I am proud of the service I did.

I had a new glass fitted to the case. This was the Achilles heel when testing the watch for watertightness. I improvised a waterproof testing machine with a Tupperware container and the freezer. My genius process is as follows: dunk the case in the water, look for bubbles. If no bubbles appear, that’s good. Shake the watch around for good measure. Then, take the watch out, dry it, and put it in the freezer for a few minutes. If you see condensation on the underside of the crystal, there has been water ingress. Dry the case, try improve the watertightness by lubing gaskets and then try again. My watch failed every time. Granted, there was only a tiny bit of condensation, but I wasn’t having it. I keep my vintage watches far away from water anyways. It was a fun experiment. If I had a slightly bigger glass fitted, it would probably make the watch seal tighter. I am fine with how it is currently.

The date jumper wheel was not the only part that I replaced. I did something that I have never done before and replaced the entire dial. Some may say that this destroys the character of a watch and that I should be hung, drawn and quartered above a giant fire, but to those I’d say “it is what it is.” I have kept the original, damaged dial, of course. My watchmaker has a privilege no one else in the world has. He has not one, not two, not three, but four Chamber of Mines Safety Watches, all in a little tobacco tin. He had a few dials, so I bought one that was in better condition than mine from him. A new crystal and a new dial can make a watch look brand new. I can say that it has something to that effect on mine.

I put a new strap on, as the old one was rubbish and smelled like an unwashed person with diarrhoea smearing blue cheese into themselves. Pardon the colourful words.

I had a nice rubber strap laying around. I had it on my Nivada SP Aquamar before giving it to my father, because the strap didn’t fit him. Some new spring bars went in and voila, I had a very clean 1977 Ernest Borel Chamber of Mines Safety Competition Watch which costed me a day’s work and less than 40 USD total. My sincerest thanks go to my watchmaker who helped me out immensely on this. This wouldn’t have been possible were it not for him and his kindness and expertise.