One of the problems with having opinions about everything is that sometimes you have to express that opinion, even when you should not. And having expressed this opinion about a trivial matter, such that it would not cross most people’s minds, you end up with a vintage watch that you did not intend to buy. Oh no! The vintage watch collector bought another vintage watch and now will attempt to justify it.

I buy watches from online retailers, brick and mortar shops, estate sales, and for years now eBay auctions. I aways have an eBay tab open in my browser and measure my interest in watches (the watch sickness) by how many watches I have saved in my “Watchlist” to monitor auctions. Do you know how many individual auctions you can monitor at one time? The answer is four hundred. Ask me how I know. Currently, I am monitoring eight auctions, and only a handful of watches. I have developed some sort of inner peace (for the moment). I don’t always monitor items with the idea of bidding on them. Sometimes I am just curious about what the final price may be. It is my way of looking at the market without having to subscribe to a service.

Which leads back to this Newport, why was I looking at it. It was because the listing was a mess. It had a reserve that had not been met. I have an opinion about reserves: don’t use them on watches that don’t have a fairly healthy market and fan base in the community. Vintage Tudor, Le Coultre, Zenith, those brands justify a reserve being placed on an auction. That way the seller is protected from bad luck in the timing of the auction. You guarantee a minimum price. But an unknown brand? All that a reserve would do is scare off the curious. Newport wasn’t a brand with a loyal following. Before this had you ever heard of them? I hadn’t.

Another problem with the listing was its accuracy. When a caseback states “Stainless Steel Back” that means that the rest of the case is electroplated brass. There was a steel shortage caused by the Second World War that lasted for more than a decade. Brass cases were the norm until the late 1950’s and persisted in less expensive brands longer. I put this watch in an era when having a brass case was an economic choice rather than a necessity.

I felt like I had to tell the seller these things. I felt the softest way to deliver the message was to send in a below reserve bid with an attached message. The auction had been up for nearly a week, and I was only the second person who had viewed it. The reserve was keeping casual bidders away and there were no devoted Newport fans out there. And it was chromed, which is ok, but don’t call it steel.

Did the seller internalize my minor quibbles with the listing and relist it with an eye towards maximizing its exposure? No, he merely countered with a few dollars more and the Newport was now my problem. I really showed him. It really only needed a slight buff with Polywatch.

So, what did I get for my pedantry? A well-made mid-century watch that is in remarkably good shape. It doesn’t look like it was ever anyone’s daily watch, it doesn’t have that sort of wear. It is not a high-end watch, it is surprisingly thick, nearly twice the thickness of my automatic Eterna. Thinness was premium in the 1950’s and 1960’s. In a way this watch feels almost modern, like the compromises one must make to accommodate a NH35.

Newport was a brand of R. Gsell & Co., Inc. founded in 1922 in New York City by Roland Gsell. Roland was born in St. Imier, Switzerland in 1896 and trained as a watchmaker. He and his wife Freya immigrated to the United States in 1918. He became an American citizen the same year that he founded his eponymous watch company. R. Gsell & Co. remained headquartered on Maiden Lane in Manhattan until his retirement in the 1970’s. The family lived in Scarsdale, New York. Roland was a former president and board member of the Jewelers Security Alliance and had served on the War Production Board during World War II. He seems to have lived a full life to the age of 95.

Newport was just one of the many brands produced by R. Gsell & Co. Mikrolisk has listed over eighty brands under the Gsell name. The ones that I have seen before are Olympic and Lafayette. There are some nice Olympic models from the 1940’s and 50’s. Lafayette was a pin pallet budget brand. They look nice, but you know, pin pallet.

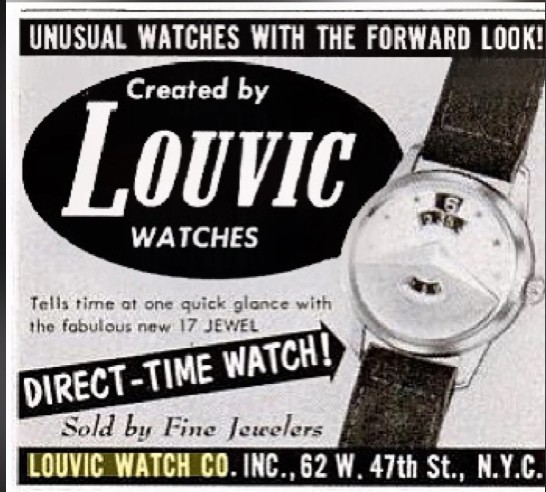

The American watch industry in the 20th Century, or least the first seven decades of it, seemed to fall into three broad categories of business models. The first was the soup to nuts integrated company. They built and cased their own movements in the United States. This was how Waltham, Elgin, and Hamilton began (not how they ended). Others would build movements in Switzerland in their own factories and import them to be finished and cased in the United States. This is mostly what Bulova and Gruen did. I say mostly because Bulova built its Accutron movements in the U.S. The third category were companies, like Gsell, that would buy movements from Switzerland and case them in the United States. Later, they would also buy movements from West Germany, England, Japan, and France. The bigger names were Benrus, Helbros, Clinton, and Welsbro. But there were hundreds more, mostly based in Manhattan, like Banner, Bergman, Gothic, Gotham, and Louvic.

(I could not find any Gsell brand print ads.)

Gsell seemed to have two interrelated businesses. One would act as a broker for jewelers and department stores to supply them with watches and the other was to sell them directly to consumers. I think that explains all of the different brand names. A jewelry store in one part of town had one named brand, and across town, another jeweler sold another brand, both supplied by Gsell, but different enough. Gsell would take orders and then have to fill them. They would contract with the Swiss cartel (yes, called a “cartel”, not yet a dirty word). The Swiss, because they could, would not give the buyer a date of delivery. They would deliver the movements when they decided, often more than a year later. The buyer would then have eight days to pay the contract price. If payment fell outside the eight-day contractual window the buyer would lose the five percent discount on the order. That five percent discount was the profit margin for companies like Gsell. The buyer would also have to pay the tariff on the movements which in the 1940’s and 50’s would range between 60 to 80 percent of the value of the movements.

Imagine the constraints of this way of operating. The jewelry store orders twenty-five watches. The movements are noticed for delivery fifteen months later. Within eight days the money must be in Switzerland for the whole operation to be profitable. It may be two years before the watches are delivered to the store. What sort of mischief can happen in that time? At least when you wait on a microbrand it is a direct-to-consumer experience. Here an entire segment of the industry, and a sizable one, was operating like that.

Gsell lost money eight out of ten years during the 1930’s. That was the Great Depression and they survived. But a second crisis hit the watch industry in the early 1950’s and sales of all brands took a nosedive. I think that this downturn in the 1950’s was the extinction level event that reordered the watch industry in the 1970’s. The so-called Quartz Crisis is the pop quiz answer, but the meteor had already hit. Gsell improvised by moving into pin pallet movements. I touched on this 1950’s event in a older post about Benrus. I may have to revisit it to refine my thesis.

What do I really know about this Newport? Not much really. It has given me a glimpse into the vanished American watch industry. It will provide another “hit” when you search for Roland Gsell. It keeps time and maybe preserves a little memory. Not a bad investment. Consider it the “know it all” tariff that I pay.