What would it have been like to have been born in Britain in 410 A.D.? You were brought into a world that had just ended. The Romans retreated, leaving their buildings, walls, and roads, but little in the way of enduring culture. When I look at the ancient ruins of the American watch industry, I find myself in a similar situation. Before the time that I can remember popular songs on the AM radio and Saturday morning cartoons the American watch industry had vanished in any recognizable form.

We have been told simplistic answers. There is a popular YouTuber who does historical videos. His answer is the Quartz Crisis. He gets some basic facts wrong, too many facts to be able to trust his conclusion. The introduction of quartz movements by Seiko in 1969 was a watershed in the industry. It is just not a monocausal explanation for everything that happened immediately thereafter.

Most of what has been written is a “who” and “when” without much of a “why.” Dig into it a little bit and you can see the difficulty. Economies are poorly understood, even by those who have expertise in these matters. Trade policies are sold by politicians as a fix it all elixir, without any recognition of the trade-offs. Was the American watch industry murdered? Did it commit suicide, or die of old age? There is evidence for all three. While the following story is not necessarily suicide, the parties carried on for a decade afterwards, it could not have been “helpful” to any of the parties.

The Industrial Revolution was unlike any other economic change in human history since the invention of agriculture. In the United States and the world it created incredible wealth. We had our Gilded Age and “robber barons”. In 1911 the Sherman Antitrust Act attempted to keep companies from becoming monopolies of goods or services. This was strengthened by the Clayton Act in 1914. Again, in 1950 the Clayton Act was amended by Congress to prohibit certain kinds of stock manipulations. It is here that we meet the villains of our story.

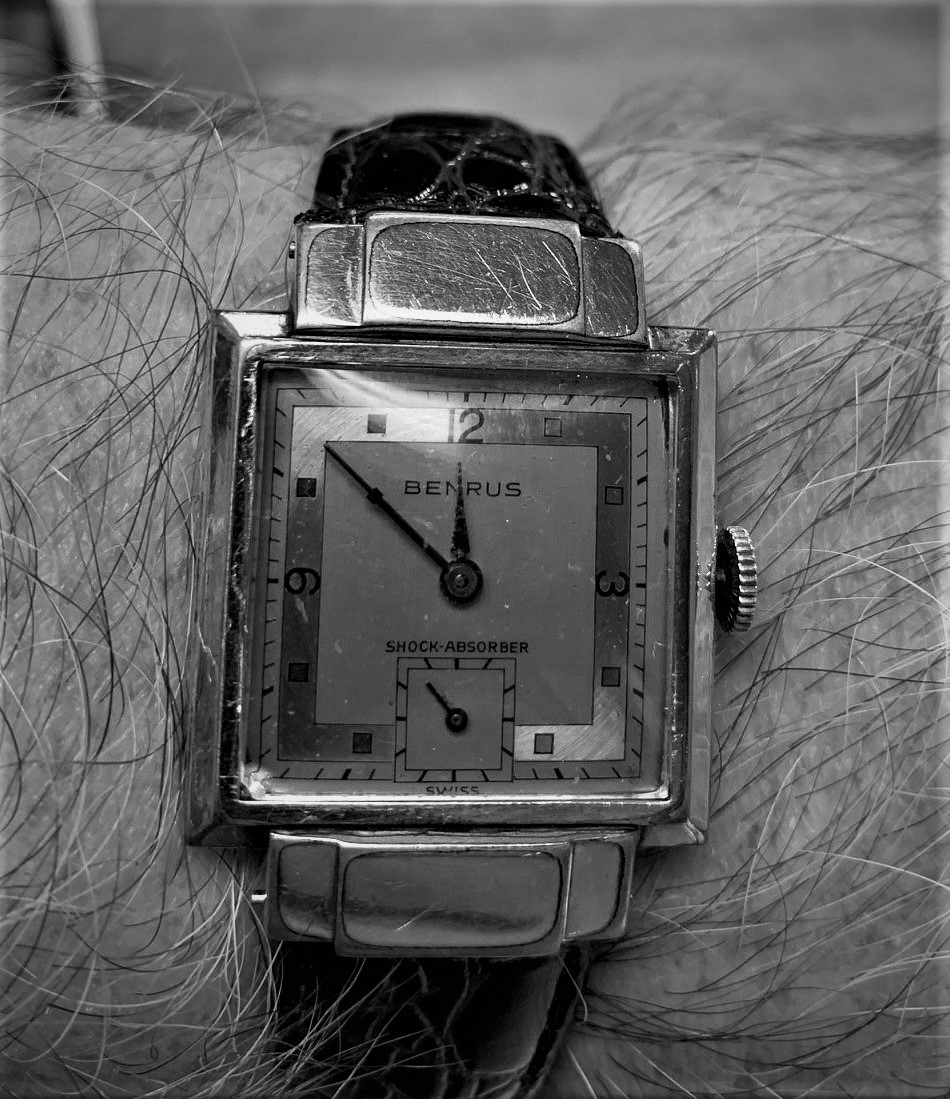

The Benrus Watch Company was founded by Romanian immigrants in New York City in the early part of the 20th Century. They started manufacturing women’s watches and transitioned to men’s watches during the 1920’s. They imported Swiss movements and cased them in New York (later Waterbury, Connecticut). This was a typical practice for most American companies after the First World War.

World War II caused a great disruption in the American and world watch industry. Some companies obtained government wartime contracts. Benrus was one of these. When the war ended the various companies jostled and elbowed to retake their pre-war positions. By the early 1950’s six companies controlled 90% of the American retail market for watches: Elgin, Bulova, Benrus, Longines-Wittnauer, Hamilton, and Gruen. Elgin was by far the largest and tripled their sales between 1946 and 1952. Waltham, perhaps the most important American watch company, was a distant seventh and would not survive the decade. Benrus, Longines-Wittnauer, and Hamilton all had about the same value of sales, well behind the top two.

We hear a lot about the Quartz Crisis, but the early 1950’s were a difficult time for the American watch industry. They had overexpanded and sales lagged when the Korean War started. Hamilton’s sales began to tumble and it started radically rethinking its business model. For the first time Hamilton began to import Swiss movements and it cased them in watches branded with the Illinois name. Hamilton had acquired the foundering Illinois in 1928. Hamilton’s stock price fell and in 1952 it showed an operational loss of $600,000 in the first quarter alone. Hamilton began to sell directly to retailers and began to sever longstanding business ties with watch wholesalers.

In 1952 Benrus’ sales were increasing. They had developed a clock for automobiles but were having a hard time finding a domestic manufacturing facility. (Automobile clocks sustained Waltham in its last decade.) This was the official Benrus story. Another story was that they had excess capital and were looking to invest it in an American company. In the early 1950’s Benrus bought a lot of Elgin stock.

But then they sold this stock, at a loss. And they started buying Hamilton stock. By June of 1952 Benrus had acquired more than 10% of Hamilton’s outstanding shares and Hamilton’s Board of Directors became alarmed. Hamilton organized a voting trust of their shares to ward off any control that Benrus might seek to exert. Benrus continued to buy shares, ultimately controlling 24% of the total. In early 1953 Benrus began its move to control Hamilton and Hamilton sued.

The automobile clock story appears to have been true, but not the reason Benrus was making this move. In 1952 the United States Tariff Commission recommended that import duties on Swiss watch movements be substantially increased. Such a policy would have made Benrus watches relatively more expensive than American made watches like Hamilton and Elgin. President Truman rejected the recommendation, but Congress looked poised to legislate the matter (Harry S Truman, friend of the Swiss watch industry, Vulcain wearer). Government intervention in markets having unintended consequences is an old story.

In order to prevail and enjoin Benrus from voting its shares Hamilton had to show irreparable harm to its business and that the actions of Benrus in buying their stock was a violation of the Clayton Act. The district court had to hold a hearing and make a finding of fact. That’s how we know about this. The watch industry is notoriously opaque. Only when facts must be proven in a public forum do we feel reasonably certain that we aren’t being spun.

The court found that Benrus had acquired enough shares that it was able to obtain a Board seat on a direct competitor. Benrus, from that vantage, could see and anticipate Hamilton’s future business plans and innovations. (Hamilton and Bulova were about to embark on the quest for electric watches which ultimately lead to, you guessed it, the Quartz Crisis.) The court found a violation of the Clayton Act and enjoined Benrus from voting its shares. The hostile takeover was averted and Benrus sold the shares.

If the case had been decided differently, we might all be discussing the merits of the Benrus Khaki Field watch and why they won’t put a decent anti-reflection coating on the crystal. This is one of the few chapters in watch history for which we can be certain of facts. It shows the fragility of the industry more than a decade before other changes transform it and sweep away many brands.