(What follows is not about watches. I could have tried a weak attempt to make some watch related reference, but it would have been transparently bad. At all historical times alluded to below you may assume that I wore a Fossil “Blue” with a green dial and a yellow fixed bezel. I am not ready for 1990’s nostalgia just yet.)

When an important historical figure is examined in the time after their passing it is often up to those who follow to make sense of their legacy. Often the person exhibits traits such as misogyny, casual racism, or antisemitism that must be addressed. It really doesn’t serve anyone to overlook these flaws. Martin Luther King was an imperfect man, not a saint. It does not detract from his greatness. We can admire Mahatma Gandhi and still be glad that we weren’t married to him. Henry Ford is problematic, important historically, but he held odious views. On the sliding scale towards Nathaniel Bedford Forrest, we excuse less and scorn more. Often what we say that “it was a different time” or that he or she “was of their time.” This is reserved for the difficult cases where we cannot explain away the negative, but all is not negative.

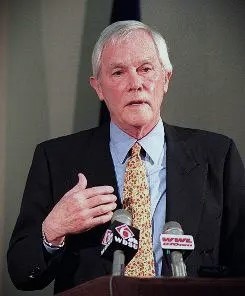

Last month one of the two most important large American city District Attorneys died at the age of 97 (Robert Morganthau of Manhattan was the other). Harry Connick, Sr. was as consequential a prosecutor as urban America has ever produced. He was controversial and divisive. He was hated and beloved. He was elected District Attorney of New Orleans in 1974 and retired in 2003. He transformed the legal landscape of his city and the United States. I will leave it to the obituary writers and historians to give you the granular details. That is not my purpose.

When I first started to practice law in the City of New Orleans, I was not a good fit for local firms. I was an outsider in a culture that strongly favored local ties. You may live there, but if you weren’t born there, well good luck. I started to doing a little criminal defense just to feed myself. I applied to Mr. Connick’s office and was essentially blackballed for practicing defense (I was later told). So, I kept practicing criminal defense and applying. I worked as a defense attorney for five years, mostly going up against his prosecutors, and eventually beating them.

The legal culture of any office, be it a firm or a governmental office, is set by its leader. The District Attorney’s Office that I fought in those years was secretive, insular, and practiced very much with an “us versus them” mentality. Those prosecutors had very little discretion, all major decisions were decided by upper management, often by Connick himself. And it was a maximalist office, meaning that the highest possible charge and punishment were pursued in all cases. There was no flexibility, sometimes even when reality intervened.

I was eventually hired in 1998 and was moved into the Trials Division. I skipped several steps due to my experience and the fact that most of the trial ADA’s had plenty of experience with me. I had a new child and needed the state health insurance and steady pay. I began to work for “the Man”.

We rarely saw Mr. Connick. He was not “Harry”. We were not his friends. He was doing us a favor by employing us. Most lawyers in New Orleans had passed through his office in the preceding twenty-four years. They all had stories, and some had scars. It was a fraternity of sorts. It was a network that an outsider like me needed for the future. I was using Connick, and he was using me.

What did he get? I could try a case with little preparation and often little sleep. I had an infant at home, and I often worked fourteen or fifteen hour days. I might try a case until 2:00 in the morning and then be expected to try another at 8:30 the next day. I did. During my time there I tried as many as seven felony trials in a month. I have twice tried two felony trials in one day (a practice later forbidden by the Louisiana Supreme Court). We had to document every case and every result. If results didn’t meet expectations, there were the inevitable consequences. Often there were late Friday afternoon firings and personnel shuffling. Fear is a motivator, for a time.

By the time that I was a prosecutor the office ethos had changed with a new generation of hires. Some of these people are still my friends. They replaced the ethically challenged and softened the office. They were fair. They knew that it wasn’t us versus them. For me it never was.

Maybe it was my time as a defense attorney, but I could never tow the Connick line of maximum punishment all of the time. Many of us worked to undermine the worst effects of this sort of maximalist approach to prosecution. For example, the law at that time for possession of cocaine did not have a “useable minimum” requirement for the drug. This meant that any residue of cocaine in a crack pipe, invisible to the naked eye, if it tested positive for cocaine could by used to prosecute a felony. The penalties for repeat offenders could be very severe. Maybe as many as 30-40% of our felony drug cases could be “crack pipe” cases. It was not usual for young men, and it has to be said young black men, to receive sentences of five to fifteen years for the invisible residue in a pipe found on or near them (this is the “mass incarceration” in its real form). My public defender and I agreed to waive the juries and try these cases before our sympathetic judge. He would find four or five men not guilty every week to eliminate his backlog of cases so that we could focus on violent crime. It took the higher-ups months to figure out what I was doing.

So, of course they ordered me to stop trying judge trial crack pipe cases. My handling of these cases was common knowledge in the courthouse and other judges asked Connick if their prosecutors could do what I was doing. Connick was not pleased. He bet one of the judges, one of his former First Assistant District Attorneys, that juries were fairer than judges and that a jury would convict on a crack pipe case. The bet was if the jury convicted then the judges would allow jury cases to continue. If the jury acquitted, then the District Attorney’s Office would charge crack pipe cases like paraphernalia cases like they did elsewhere in the state. The Assistant District Attorney that he chose for this bet was the one that caused all the problems in the first place, me. Senior management was there to watch the case to ensure that I did not throw or tank it. I played it straight and won, thereby making the unfairness continue for several more years.

Connick never mentioned it to me. In fact, I was only called to his office once in my time there. My audience was about an armed robbery suspect that I was following office policy in prosecuting. I had the evidence to convict and I was not making any plea offers. The difficulty was that a local minister had intervened for the young man. This minister was a useful liaison for Mr. Connick when he needed black votes. I was causing another problem. The young man received his measure of mercy and a generous offer.

Eventually, the cognitive dissonance was too much. I quit to join a criminal defense firm. I couldn’t play every side to get to fairness anymore. I had to pick a side.

When Connick was elected the United States was in the second decade of a crime wave that would unsettle American culture and confidence. One look at the dystopian movies of that era reflects the cultural malaise: The French Connection, Death Wish, Robocop…the list is long. In the 1990’s New Orleans was experiencing a homicide a day and was the per capita murder capital of the country, narrowly edging out Detroit for that honor. The DA thought that that barbarians were at the gate and that it was “us versus them.” Connick cut corners. The United States Supreme Court noticed and rebuked him on more than one occasion. Prosecutors in his office were credibly accused of hiding exculpatory information that may have aided defendants (Brady information). They cheated to win. Some of us cheated to keep it fair. That’s not how it should work. There should be no cheating.

I later became a prosecutor in another American city. The culture was different. There was no cheating. No one could believe my stories (and do I have stories). They had never experienced such a prosecutorial culture. They hadn’t seen the “bad old days”.

In fairness to Connick the bad old days extended to places other than New Orleans. However, the legacy of the segregated South was particularly pernicious in that city. I could say that Connick was a “man of his time” and try to excuse all the misbehavior that he permitted in order to incarcerate as many as he could. But I don’t think that captures the truth of the matter. He extended the bad old days for decades longer than any reasonable person would in a quixotic attempt to stop crime and preserve an old social order. He never stopped crime. He just meted out punishment for which there is no redress. He thought that he was the hero of the movie, only to be revealed as the villain.

And yet, he is in a small way formative in my development as an attorney and as someone who thinks about crime and punishment. My covert and overt opposition to his office and policies guided my later judgment. I can’t be the only one.

So, I hope Harry has some answers for St. Peter. It may cut down on that purgatory time (it’s a Catholic thing).

An interesting story about a awful man. I believe people like that are very unhappy within themselves. I pity them.

LikeLike